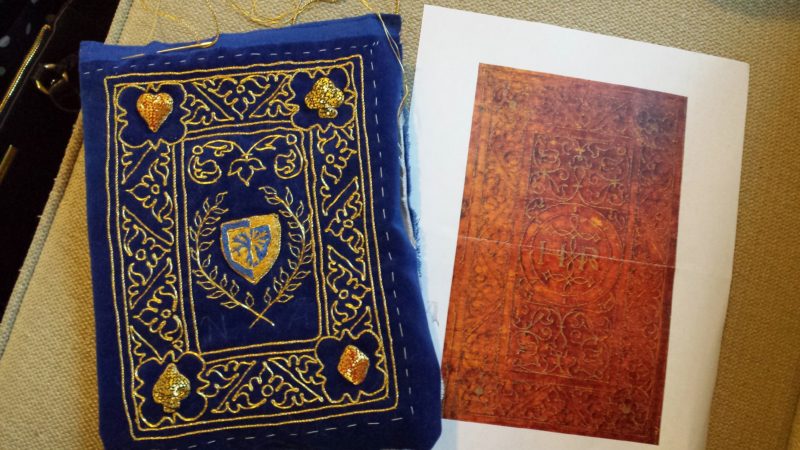

Made by Alison Choyce, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Alison Wodehalle.

This is a hand sewn, 14th century style, button front hood with liripipe. Made of a light blue linen, it has a silk tablet woven edge, and silk embroidery, wool applique and has a lining in white silk.

Hoods were part of normal everyday costume for people from all walks in life throughout the 14th century. Queen Phillipa and Princess Joan of England had hoods made for them. The French princess, Jeanne de France, and her sisters Marie and Ysabel de France had embroidered hoods made for them (Newton, 35). Chaucer dresses his Miller, one of the secular pilgrims in “Canterbury Tales”, in a blue hood. (Hodges, 201) There are extant finds of hoods for both men and women in London, Greenland, Dordrecht, and other places. Singman and McClean tell us that a female agricultural laborer earned about 2 pence per day, and a hood (probably used goods) could be purchased for 4 pence. (Singman et al, 37)

Exterior fabric: I am using a blue linen for the exterior. The fabric used in period varies depending on the wealth of the wearer. The extant finds are of wool, most of them in the Vadmal 2/2 twill of Greenland. The hoods described in records of the wealthy include hoods made of silk velvet, fine wool, scarlet and other such fine fabrics. (Newton 34-5, 54, 65; Owen-Crocker, et al Encyclopedia.) I decided on the use of the linen fabric, though not noted in period sources, since the use for this hood will be for warmer weather, and will provide me with protection from the sun, rather than from the cold.

Lining: The written evidence often lists hoods as being lined. (Hodges, 85) Newton lists many rich linings such as silk and miniver. Hodges quotes S. L. Thrupp “silk lined hoods trimmed with fur or gold thread embroidery…” (Hodges, 84) Of the extant garments, there are some that appear to have been lined. However, most of the linings have not survived the centuries, but there are traces or hints that the linings were there, such as needle marks for seams. This hood is lined with a light weight plain weave white silk.

Colors: The use of blue and white were associated with faithfulness, and purity, they were the colors of the Order of the Garter, although the blue of this Order was likely a much brighter blue than I am using. (Newton, 43) Many hoods were made by order of the king in these colors as livery for both men and women. Chaucer’s miller is wearing a blue hood, though the shade of blue is not specified, and King Arthur is always portrayed wearing blue. (Hodges, 198-201). Blue became even more popular in the 14th century, becoming a prominent color in heraldry, in stained glass (due to new processes), in illuminations, and in clothing (due to innovations in dying fabric blue). (Pastoureau, 49-60).

Tabletweaving: Silk thread tablet weaving is placed to the edge with the button holes, using 4 tablets in white. In looking at the extant finds, I do not see evidence that this same treatment was applied to the edge with the buttons, and so I did not place the tablet weaving there. On page 169 of Textiles and Clothing (Crowfoot, et al) describes in detail the finishing of the button edge which has a silk facing, but no tablet weaving; and on the same garment the buttonhole edge which, along with the narrow silk facing, has a narrow tablet woven edge, which the author believes visible mostly just to the wearer and those close to him or her, as it is so small. Textiles and Clothing also tells us that “tablet weaving was used to bind cut edges” (Crowfoot, 135) It is found often on the buttonhole edges of sleeves, and on the edges of purses. It has been found on at least two extant hoods, one in the London finds, and one in Dordrecht, Netherlands. It appears to have been kept simple, in one color with forward turns of the tablets, using either 2 or 4 tablets for a very narrow band. It seems to be mostly utilitarian, and provides strength to the fabric that has been cut for buttonholes.

Buttons: The buttons on this hood are similar to buttons that are extant to the 14th century. The extant buttons have a pierced saltire design on them, and are made of brass. The buttons I used are metal, though not brass, have a pierced star design on them, and are of similar shape. “Metal Buttons” describes an extant button as, “biconvex; hollow; a voided saltire, each arm with a band of drilled open work, two quadrants have a trefoil of drilled openwork, while the other two are filled with pits”. The photo bears striking similarity to these modern buttons.

Embroidery: There are many depictions in the art of the period, of what appears to be embroidery circling the hem or the skirt of the hood. I am not sure what this quote refers to “the twelve hoods with their white borders” (Newton 42), but it could be this type of embroidery. It could also be the edge made by “foot weaving” noted in the Norse finds. (Ostergard, 207-9; Fransen et al, 32) Newton repeatedly refers to embroidery quoting medieval writers in their observations of rich silk embroideries, heavily set with pearls and precious stones. Hodges further describes the same excess, “they wore silk embroidered hoods” speaking of wealthy peasants, who are rejecting sumptuary laws. (Hodges, 197).

Hodges tells us, “There were three fashionable styles of embroidery designs in the late 14th century, geometric patterns, heraldic devices, and naturalistic motifs.” (Hodges, 61) Pearls were often used to embellish embroidery, especially seed pearls. (Staniland, 46-7)

Inspiration for the design on this hood is from the Luttrell Psalter.

My thoughts at the conclusion:

I know the question is often asked if you felt a connection to the medieval artisans who might have created a similar product. I am not sure about the word ‘connection’, but I do think about differences while I work. Like how did medieval silk workers keep their fingers from being dry and creating little pulls in the thread? They must have moisturized, maybe with a clean lard or, a beeswax moisturizer or something. I may need to research this someday. And I think about how lucky I am that I am doing this by choice, for myself or for someone I ‘want’ to give this to, rather than because I have to, to earn a living. I am grateful for artificial lighting. Also, I need glasses to do this work, and depending on my situation in period, I may not have had magnifiers, and may have been unable to do this type of work by this point in my life.

The tablet weaving was placed without much difficulty. However as I look at the picture of the extant sleeve, I see that the weaving is more front facing than mine is, and that the buttonholes come closer to the edge than mine do. I will aim for that look in my next hood. Also, the bottom corner of the extant garment, is more rounded than the lower corner of the buttonhole edge of this hood.

I did make a change in the embroidery from my original plan. I decided to add the applique, because although the shape and color of the design were part of the original, I was not satisfied with the look of those areas filled with split stitch, silk thread embroidery. That is the only change in my plan for this project.

Bibliography:

Egan, Geoff, and Frances Pritchard. Dress Accessories, C. 1150-c. 1450. London: H.M.S.O., 1991. Print.

Chaucer, Geoffrey, and Ralph Hanna. The Ellesmere Manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales: A Working Facsimile. Woodbridge, Eng.: D.S. Brewer, 1990. Print.

Collingwood, Peter. The Techniques of Tablet Weaving. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1982. Print.

Crowfoot, Elisabeth, Frances Pritchard, and Kay Staniland. Textiles and Clothing: C.1150-c.1450. London: HMSO, 1992. Print.

Forgeng, Jeffrey L., and Will McLean. Daily Life in Chaucer’s England. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1995. Print.

Fransen, Lilli, Anna Nørgaard, Else Østergård, and Shelly Nordtorp-Madson. Medieval Garments Reconstructed: Norse Clothing Patterns. Aarhus [Denmark: Aarhus UP, 2011. Print.

Hodges, Laura F. Chaucer and Costume: The Secular Pilgrims in the General Prologue. Cambridge [England: D.S. Brewer, 2000. Print.

“Metal Buttons: C.900 BC – C. 1700 AD [Paperback].” Metal Buttons: C.900 BC. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Sept. 2013.

Newton, Stella Mary. Fashion in the Age of the Black Prince: A Study of the Years 1340-1365. Woodbridge: Boydell, 1980. Print.

Owen-Crocker, Gale R., Elizabeth Coatsworth, and Maria Hayward. Encyclopedia of Dress and Textiles in the British Isles C. 450-1450. Leiden: Brill, 2012. Print.

Spies, Nancy. Ecclesiastical Pomp & Aristocratic Circumstance: A Thousand Years of Brocaded Tabletwoven Bands. Jarretsville, MD: Arelate Studio, 2000. Print.

Staniland, Kay. Embroiderers. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1991. Print.

Østergård, Else. Woven into the Earth: Textiles from Norse Greenland. Aarhus: Aarhus UP, 2004. Print.