This is a Tudor period style partlet, made of white linen with blackwork embroidery in silk thread. The tie strings at the neckline are linen fingerloop braids, done in a round of 8. This was made for a friend on the occasion of her elevation to the Order of the Laurel (a recognition in the organization www.SCA.org). This purpose guided some of the decisions, and impacted the amount of time available.

Evidence for embroidered partlets in the Tudor era: Partlets were well known throughout the Tudor period, and beyond England to western Europe. In the reign of Henry VII from the Great Wardrobe accounts, we know that the late Countess of Suffolk received a partlet in December 1501 with her allotment of clothing as a servant of the Queen (Johnson, 2011, p. 23). 76 years later in 1577, Queen Elizabeth’s agent wrote that the queen “would gladly have a suit of her own linen partlets” (Arnold, 1988, p. 132). They became ubiquitous, “Partlets and neckerchiefs were worn both over and under the bodies to fill in the neckline” (Mikhaila & Malcolm-Davies, 2015, p. 30). We know from the art and from wardrobe accounts that they were either of white linen which was sometimes embroidered, or of black velvet. As for the embroidery, we have much art with blackwork embroidery on partlets (see attached images at the end). Gostelow tells us “These partlets were often delicately edged with blackwork embroidery, sometimes designed to match the stitching on cuffs and sleeves (Gostelow, 1998, p. 71).

Fabric: White linen was often used for partlets, as was black velvet. Linen was chosen for this project so the recipient could have year-round use of it, as black velvet might be difficult to wear in summer. Mikhaila & Malcolm-Davies discuss different types of linen used in the wardrobe accounts, and late Tudor period seems to have preferred thin see-through linen, known as ‘lawn’, however that weight of linen does not appear to have been embroidered, and the extant pieces of clothing items with blackwork embroidery are made of opaque linens (Mikhaila & Malcolm-Davies, 2015, p. 36-37). Johnson tells us that linen for clothing was plain woven, and that linen for show would be bleached white (Johnson, 2011, p. 15).

Lining: Linings were used at least on early period partlets. Referring to the time prior to Elizabeth I’s reign, Arnold states “the earlier partlet seems to have been a more solid arrangement as it was lined (Arnold, 1988, p. 133). The Tudor Tailor also discusses linings, explaining that it protects the decorated layer from wear and grime (Mikhaila & Malcolm-Davies, 2015, p. 43) This partlet is lined with the same fabric as the exterior of the partlet.

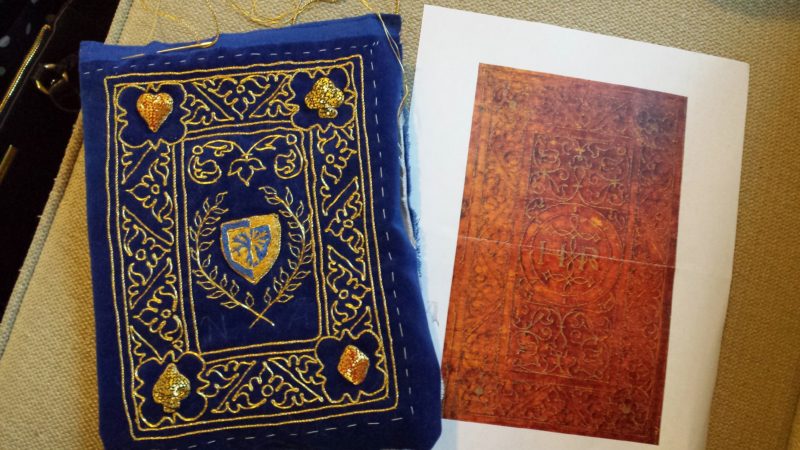

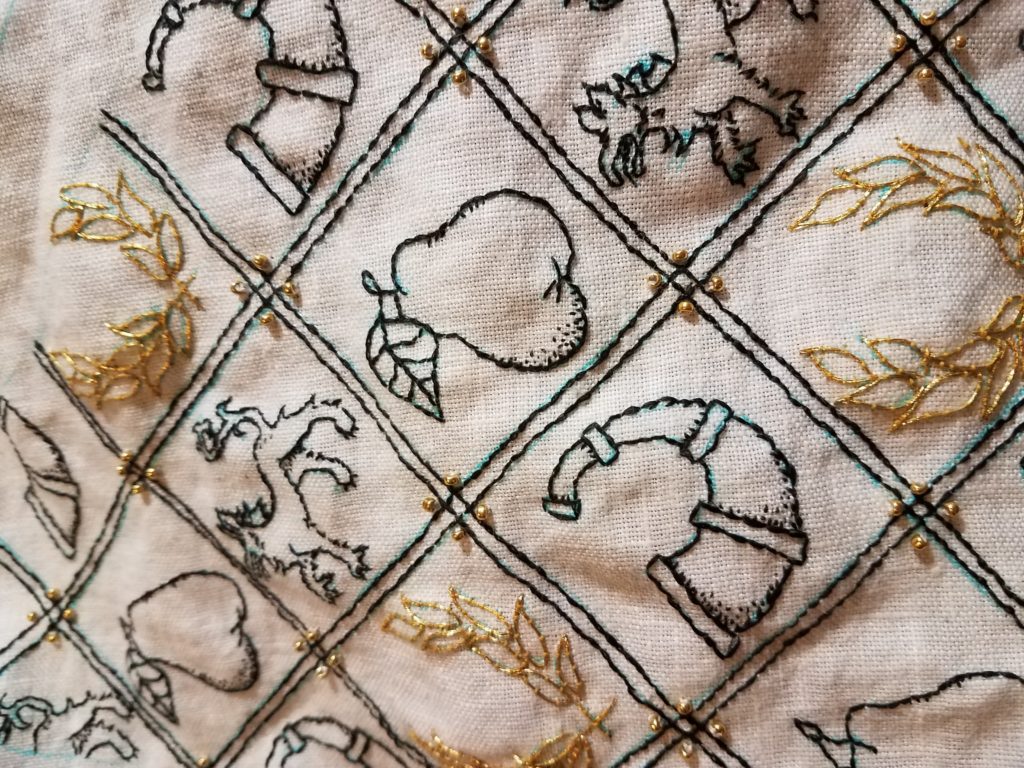

Embroidery: “…Embroidery was restricted to linen garments such as smocks, shirts, and partlets. Blackwork and whitework were the most common forms, the designs being simple geometric patterns, followed by arabesque, and naturalistic styles. Later blackwork was embellished by silver or gold thread” (Mikhaila & Malcolm-Davies, 2015, p. 43-44). The partlet here is embroidered with blackwork figures of pears, hunting horns, tygers, and goldwork laurel wreaths, with green thread creating a larger laurel wreath around the base of the garment. The four figures mentioned above were placed on a divided field of diamond shapes. Mrs. A. H. Christie discusses the use of repeating elements, stating “the repeating element is perhaps a symbolic figure, a heraldic shield, or it may be some geometrical form that supplies the motif” (Christie, 1915, p. 56). This author further tells us that the embroidery is more interesting if the repeating pattern contains some variety, and if the ground is divided in some way, giving the example of diagonal lines (Christie, 1915, p. 58).

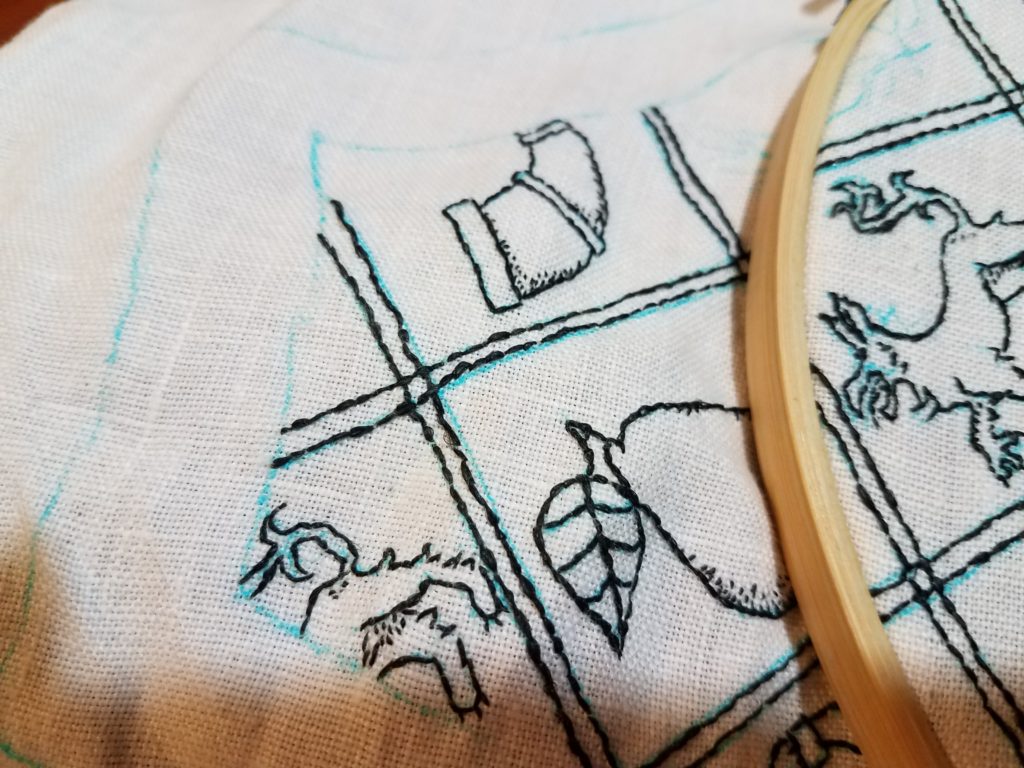

The style of blackwork needed to be able to be done on a plain weave linen, rather than an even weave. After searching for examples of Tudor period blackwork, a women’s coif circa 1600 presented a beautiful example of speckled blackwork, where the design was created in outline using stem and/or back stitch, and the figures are given dimension by using tiny speckling stitches to provide shadow. Gostelow explains, “Speckling or ‘seeding’ can also be known as ‘dot stitch’. Tiny straight stitches, worked either at any angle or in geometric formation, provide a most effective filling” (Gostelow, 1998, p. 90).

Ties: The ties at the neck opening were made using fingerloop braids of white linen thread, using the pattern for a ‘lace bend round of 8 bowes’ in the Fingerloop Braid issue of the Compleat Anachronist (Swales & Kuhn Williams, 2000, p. 35).

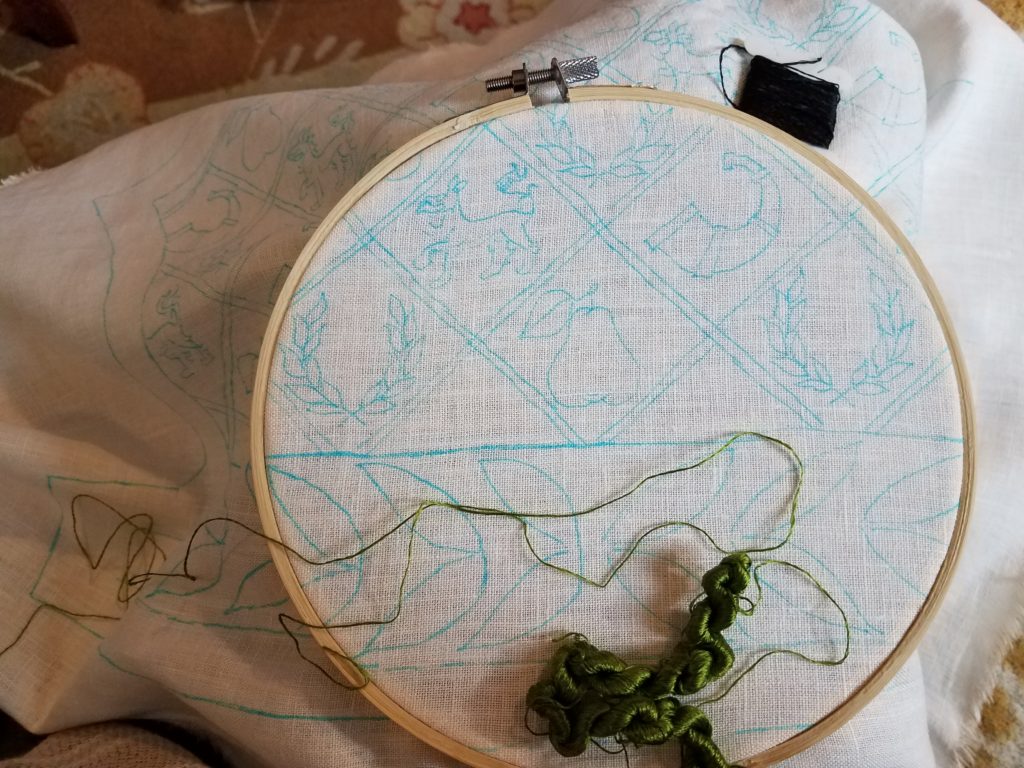

After the pattern was determined, it was drawn out on paper at 1:1 scale, and traced using a light box onto the uncut fabric. The embroidery was completed, and the partlet then cut out and assembled by hand with white linen thread. Seams were joined with a running stitch, then flat felled to keep from raveling. The lining was assembled in the same manner and joined to the outer decorative layer. All threads were waxed using beeswax. “Before use, linen or silk thread was passed through a lump of beeswax. This strengthened it and helped prevent knots and fraying” (Mikhaila & Malcolm-Davies, 2015, p. 42). The collar has a purchased lace applied as time would not permit making the lace for the edging. The collar was box pleated, and attached between the exterior and lining layers. The ties were placed as the collar was attached. The finished partlet was then ironed and was ready to present to the recipient.

fabric with pattern on it:

My thoughts on conclusion: From the time the decision was made to make a partlet until the date it was needed by, there were two months to complete the work. The embroidery took about 180-200 hours of work, with a little more time needed for the design, and the assembly. This had a large impact on how detailed the piece was able to be, as well as on the use of the light box to trace the pattern, being a purely modern method. I would love to try the prick and pounce method of transferring the design to the fabric, and will do so with a future project. I would also have liked to add more detail to the diagonal lines that separate the elements of the design, perhaps by making them as vines. And, lastly, I would have liked to use more extensive speckling as a technique to add shadow and depth to the elements of the design.

I like the appearance of the alternating pattern of goldwork and blackwork. The use of the gold glass beads, while used within the Tudor period, are much less noticeable than spangles might have been. I would try to obtain spangles for any similar project in the future.

Overall, I am pleased with the final product. I researched in advance of starting the project, and while some choices were guided by both limited time and the designated use of this partlet, the remainder of the decisions were guided by studying blackwork embroidery and linen partlets in the Tudor period. This allowed the partlet to bear resemblance to those found in the art of the era.